Get yourself into the Riparian Zone

Land close to water is typically constrained by flooding issues and zoned for low-risk developments. But in response to rising demand for housing, residential developers are now viewing these sites with opportunistic eyes and taking advantage of the amenity benefits a development near water can offer. Northrop Principal, Mal Brown identifies some of the risks associated with waterfront land and how developers can equip themselves to tackle these risks.

As we seek to develop and redevelop land to satisfy Sydney’s housing needs, residential developers are reconsidering these gorgeous waterfront locations, previously deemed too risky. However, land that is situated close to water comes with tight constraints and is fraught with issues for developers who may not understand the legislative and policy context or if their due diligence on the site prior to purchase was inadequate.

In NSW, Waterfront land is controlled by the Water Management Act and administered through WaterNSW. WaterNSW have prepared ‘Guidelines for riparian corridors on waterfront land’ to assist in the interpretation of the Act. Waterfront land is defined as any frontage to a river, creek or estuary. Often, the default for determining waterfront land is its mapping as a ‘blue line’ (watercourse) on the 1:25,000 topographic map.

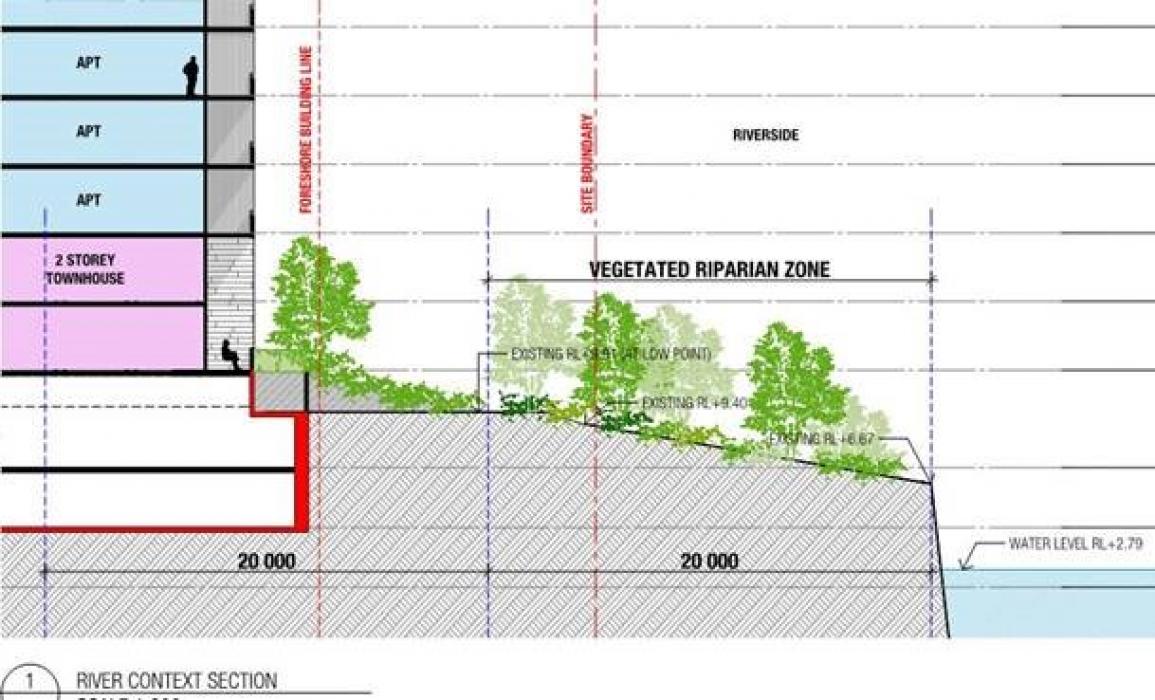

When a development is adjacent to waterfront land, setbacks known as Riparian Zones are required to protect this land. These zones can be up to 40 metres from the highest part of the waterway bank. They may also override property boundaries, so in many instances, a portion of land is excluded from development. It’s likely to come as a surprise to a developer who assumed that all the land was available. Negotiation with WaterNSW is possible on site-specific, merit-based assessment. However, the Act and Guidelines will typically win the day.

Developers should look to conduct a riparian assessment as part of their due diligence. The earlier the site is fully understood, the better. While issues arising after purchase will be a setback, there are several measures developers can take to avoid costly project delays.

Engage a waterways expert

Aspects of the Guidelines provide some flexibility for developers. The ‘blue lines’ are produced by cartographers, not waterways experts. It is possible to have an expert assess a drainage line. If there is no evidence of stream processes occurring, then the watercourse classification may be void. Typically, this would only apply to the upper parts of waterways, in grassed drainage lines with intermittent water flow.

Offsetting

A riparian corridor may be narrowed in one part of a site if similarly widened in another – it’s known as the averaging rule. Depending on the width, developers may retain some infrastructure in the zone, such as shared paths, detention basins or essential services.

Rehabilitation or revegetation

There is also scope to propose improvements (rehabilitation and revegetation) to the inner half of the riparian zone, which counts as an offset to development footprints in the outer half. A recent development proposal in Liverpool was able to achieve maximum offset through a concurrent application to revegetate the inner 50% of the zone. It was the determining factor in gaining project approval from WaterNSW.